Explorations in Wyoming History

The following links will take you to studies I have prepared focusing on aspects of Wyoming history from well before Wyoming achieved territorial status to the middle of the twentieth century and into the Cold War. While these essays were not developed, and are not presented, as sequential chapters in the history of the state, they do attempt to examine some of the critical issues shaping Wyoming’s evolution. There is an important exception, however. They do not in any instance move political events, at least in a narrow, partisan, institutional sense, to the center of attention. Government policy and programs, state and local elections, and debates over the course of public purpose all figure in to the accounts that follow, but the focus in these studies is on the people of Wyoming whose lives, for two centuries or more, have been at the center of the processes by which the Wyoming that we know has taken shape. They have shaped those processes and they have been shaped by them. Those people were more than a backdrop to political history. They were what Wyoming history might really be all about.

The essays explore issues of private and public life in Wyoming. They include long examinations of farming, ranching, and homesteading in Wyoming and of the role of federal projects in fighting the Great Depression and modernizing the institutions of life from the 1920s to World War II, a study of the way Fort Laramie both reflected and influenced social change in the nineteenth century. I have also included shorter discussions examining the importance of F. E. Warren Air Force Base as it shaped Cheyenne and the state (and vice versa) in the Cold War. There is also a link to my article on how World War II impacted Wyoming. There are others and there will be more. There will be some discussion of the Oregon – California Trail in Wyoming. The most recent work comes up to 2015 (OK, maybe just to 2012) with a study of the evolution of the campus of the University of Wyoming. There will be more. Check back from time to time to see what I have been able to post.

A word about the focus of my research and writing in Wyoming: Amidst all the large and powerful forces for change in the state, it is sometimes tempting to see the pattern of history as simply that of “progress,” as the unfolding of an inexorable, inevitable cycle of growth in which life became better and better—meaning it led us to where we are today. Given the changes in technology and the growth in the economy, at least on some aggregate level, this is understandable. There are many problems with that perspective, however, and this collection of essays modestly seeks to avoid those problems and to be sensitive to the frustrations and pains of social change, to honor the homesteader who was dispossessed and foreclosed as much as the powerful people whose empires thereby grew, to value the work of the miners laboring in the bowels of the earth as much as the investments of the mine owners who never breathed the coal dust or felt the singe of the explosion, and more generally to accord dignity and respect and even sympathy to all those who found themselves in the maw of the powerful forces and engines of social change.

Which then brings me to the general thesis of this collection of studies. If not “progress," what is the pattern? I try to be open about this and not excessively restrictive. After all, the history of the various and diverse peoples whose lives make up Wyoming is a complex history and cannot be reduced to a single pattern. And the changes that have taken place over the past two hundred years, from the fur trade to the age of the Internet, have been equally complex and nuanced and are not susceptible (although some have tried) to being reduced to static, arbitrary, and ultimately questionable categories and slogans. That said, there is still a large pattern that can be discerned in Wyoming history, and sometimes that pattern has been repeated at different times and different places in the state. Fundamentally, the pattern has been that of transformation, a constant process of transformation, a transformation in the way people lived and worked, made their livings, raised their children, looked to the future, and found purpose and meaning in each day’s labors. At one level, it has been a transformation from isolated lives (whether lonely or fulfilling) and communities (whether villages or neighborhoods or actual cities) to lives that are increasingly connected to those of others across the county, across the state, across the nation. On another level it has been a transformation from living a life of relative autonomy, dependent upon individual talents and strengths and the variables of family and weather and the circumstances of landholding, to living a life increasingly dependent upon vast impersonal markets and the decisions of others elsewhere. How beneficial that transformation has been depends largely on one’s view of the proper role of the individual and of the public in the larger economy, the purpose of organized society, and, in fact, the fundamental question of the nature of the human condition. For my part, I attempt to explore those issues in these essays, sometimes explicitly and sometimes only by implication.

Wyoming, with a population that only recently exceeded a half million, is not only the smallest state in the nation, but is also smaller than a number of American cities. It thus affords a precious opportunity to explore state and national issues with the tools and perspectives of the social historian, perspectives that allow a sensitivity to the lives of real people and real places alongside historical abstractions.

Some of the essays in the following links were prepared as parts of surveys of historical properties or as nominations of some properties to the National Register of Historic Places—or helping properties be recognized by some other designation in the National Register and related programs. In these discussions, however, it is seldom that the building itself is the strict focus; i.e., in my work it is seldom the case that a place is important solely because of its architectural features. Rather, in these essays there is a larger social significance that the building represents that makes it important and worthy of recognition. It may be a place that is nationally important, such as the Murie Ranch near Moose where the post-World War II wilderness movement found a home and nerve center. It may be much more modest, such as a small, old motel that provided its owners a source of income while also reflecting the shift of its community’s economic base from agriculture to tourism. It may be the county library or the public school or local park where people endeavored to build a socially richer and more satisfying life for themselves and their children, using public programs or private initiative to fulfill basic social responsibilities. In these instances, the buildings and other structures are less important for themselves than they are for what they represent in the purpose and consequence of their construction and for what happened inside, and outside, their walls. By looking at these “historic places” we can shed light on the history of Wyoming’s people.

As a starting point, I want to share some perspectives on the problem of doing history and especially of doing state and local history. This all comes down to the problem of context. This will admittedly be of interest especially to historians, but I encourage others to look at these discussions too in order to find out a little more about what it is that historians actually do. Hint: it isn’t just a matter of writing down events, names, and dates. It’s an effort to identify patterns of social change and to explore their meanings.

Explorations in Wyoming

History

These studies are arranged in a roughly chronological order, which is to say they examine aspects of Wyoming history in a developmental or evolutionary sense, looking at change over time. The circumstances of life underwent a continuing process of transformation and a chronological approach helps to identify the processes of social change in Wyoming. Only a few of the links below are live right now. I am working to add more as I can, so check back when you can to see if there has been anything new added.

The essays explore issues of private and public life in Wyoming. They include long examinations of farming, ranching, and homesteading in Wyoming and of the role of federal projects in fighting the Great Depression and modernizing the institutions of life from the 1920s to World War II, a study of the way Fort Laramie both reflected and influenced social change in the nineteenth century. I have also included shorter discussions examining the importance of F. E. Warren Air Force Base as it shaped Cheyenne and the state (and vice versa) in the Cold War. There is also a link to my article on how World War II impacted Wyoming. There are others and there will be more. There will be some discussion of the Oregon – California Trail in Wyoming. The most recent work comes up to 2015 (OK, maybe just to 2012) with a study of the evolution of the campus of the University of Wyoming. There will be more. Check back from time to time to see what I have been able to post.

A word about the focus of my research and writing in Wyoming: Amidst all the large and powerful forces for change in the state, it is sometimes tempting to see the pattern of history as simply that of “progress,” as the unfolding of an inexorable, inevitable cycle of growth in which life became better and better—meaning it led us to where we are today. Given the changes in technology and the growth in the economy, at least on some aggregate level, this is understandable. There are many problems with that perspective, however, and this collection of essays modestly seeks to avoid those problems and to be sensitive to the frustrations and pains of social change, to honor the homesteader who was dispossessed and foreclosed as much as the powerful people whose empires thereby grew, to value the work of the miners laboring in the bowels of the earth as much as the investments of the mine owners who never breathed the coal dust or felt the singe of the explosion, and more generally to accord dignity and respect and even sympathy to all those who found themselves in the maw of the powerful forces and engines of social change.

Which then brings me to the general thesis of this collection of studies. If not “progress," what is the pattern? I try to be open about this and not excessively restrictive. After all, the history of the various and diverse peoples whose lives make up Wyoming is a complex history and cannot be reduced to a single pattern. And the changes that have taken place over the past two hundred years, from the fur trade to the age of the Internet, have been equally complex and nuanced and are not susceptible (although some have tried) to being reduced to static, arbitrary, and ultimately questionable categories and slogans. That said, there is still a large pattern that can be discerned in Wyoming history, and sometimes that pattern has been repeated at different times and different places in the state. Fundamentally, the pattern has been that of transformation, a constant process of transformation, a transformation in the way people lived and worked, made their livings, raised their children, looked to the future, and found purpose and meaning in each day’s labors. At one level, it has been a transformation from isolated lives (whether lonely or fulfilling) and communities (whether villages or neighborhoods or actual cities) to lives that are increasingly connected to those of others across the county, across the state, across the nation. On another level it has been a transformation from living a life of relative autonomy, dependent upon individual talents and strengths and the variables of family and weather and the circumstances of landholding, to living a life increasingly dependent upon vast impersonal markets and the decisions of others elsewhere. How beneficial that transformation has been depends largely on one’s view of the proper role of the individual and of the public in the larger economy, the purpose of organized society, and, in fact, the fundamental question of the nature of the human condition. For my part, I attempt to explore those issues in these essays, sometimes explicitly and sometimes only by implication.

Wyoming, with a population that only recently exceeded a half million, is not only the smallest state in the nation, but is also smaller than a number of American cities. It thus affords a precious opportunity to explore state and national issues with the tools and perspectives of the social historian, perspectives that allow a sensitivity to the lives of real people and real places alongside historical abstractions.

Some of the essays in the following links were prepared as parts of surveys of historical properties or as nominations of some properties to the National Register of Historic Places—or helping properties be recognized by some other designation in the National Register and related programs. In these discussions, however, it is seldom that the building itself is the strict focus; i.e., in my work it is seldom the case that a place is important solely because of its architectural features. Rather, in these essays there is a larger social significance that the building represents that makes it important and worthy of recognition. It may be a place that is nationally important, such as the Murie Ranch near Moose where the post-World War II wilderness movement found a home and nerve center. It may be much more modest, such as a small, old motel that provided its owners a source of income while also reflecting the shift of its community’s economic base from agriculture to tourism. It may be the county library or the public school or local park where people endeavored to build a socially richer and more satisfying life for themselves and their children, using public programs or private initiative to fulfill basic social responsibilities. In these instances, the buildings and other structures are less important for themselves than they are for what they represent in the purpose and consequence of their construction and for what happened inside, and outside, their walls. By looking at these “historic places” we can shed light on the history of Wyoming’s people.

As a starting point, I want to share some perspectives on the problem of doing history and especially of doing state and local history. This all comes down to the problem of context. This will admittedly be of interest especially to historians, but I encourage others to look at these discussions too in order to find out a little more about what it is that historians actually do. Hint: it isn’t just a matter of writing down events, names, and dates. It’s an effort to identify patterns of social change and to explore their meanings.

Explorations in Wyoming

History

These studies are arranged in a roughly chronological order, which is to say they examine aspects of Wyoming history in a developmental or evolutionary sense, looking at change over time. The circumstances of life underwent a continuing process of transformation and a chronological approach helps to identify the processes of social change in Wyoming. Only a few of the links below are live right now. I am working to add more as I can, so check back when you can to see if there has been anything new added.

Photo: Fort Laramie store and other buildings, with Bedlam in background at left. Photo: © Michael Cassity.

Fort Laramie's People: An Exploration in Historical Context

This book-length study is an examination not of military operations and deployments at Fort Laramie, but of the contours of social change there. In the post's brief (four decades) history, it both witnessed and shaped the transformation of Wyoming, effectively bridging the social orders of the native tribes and the fur trade at one end and the making of modern Wyoming--and its social tensions--at the other end.

Transforming Peoples and Institutions: The Oregon - California Trail in Wyoming, 1840 to 1867 (Project in progress!)

This is an examination of places along the trail in Wyoming, actually a major thoroughfare, showing how the evolving road transformed not just the landscape but the social and economic institutions and relations of pre-territorial Wyoming. (I will post here when the study, anticipated to be book length, is complete. Meanwhile, patience, patience.)

Homesteading, Ranching, and Farming in Wyoming

A large part of the history of what many call "the cowboy state" involves agriculture and the relationship of Wyoming's population to living and producing on the land. Much of that history has been episodic in nature or local to the extreme, and this study endeavors to identify the large patterns of social, economic, technological, and political change in Wyoming homesteading, ranching, and farming. In other words, this is not just a study of ranches and farms, but a study of rural Wyoming and the promise and problems of that life, for a century (actually more). One way to think of it is this: the history of Wyoming (including before there was a Wyoming) is a history with two general, broad patterns. Up until the 1930s it was a pattern of migration to Wyoming and to Wyoming's farms and ranches; since then, however, there has been a steady flow of people from the land. Why is that? What does it mean for the rest of us? This link will take you to a page that was prepared for the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office and includes a number of parts. The core of it, however, is my book-length study, Wyoming Will Be Your New Home . . . : Ranching, Farming, and Homesteading in Wyoming, 1860-1960.

The Lives of Coal Miners in Wyoming in the Early Twentieth Century: The Case of Sublet Mine No. 6

Before strip mining became the dominant system of coal production in Wyoming, underground mines that extracted the coal from its seams, carried it to the surface, and loaded it into railroad cars defined the lives and work of people from a multitude of cultures. This looks at the development, the technology, the life and labor, and the decline of one mine, a mine that operated north of Kemmerer from 1913 to 1927.

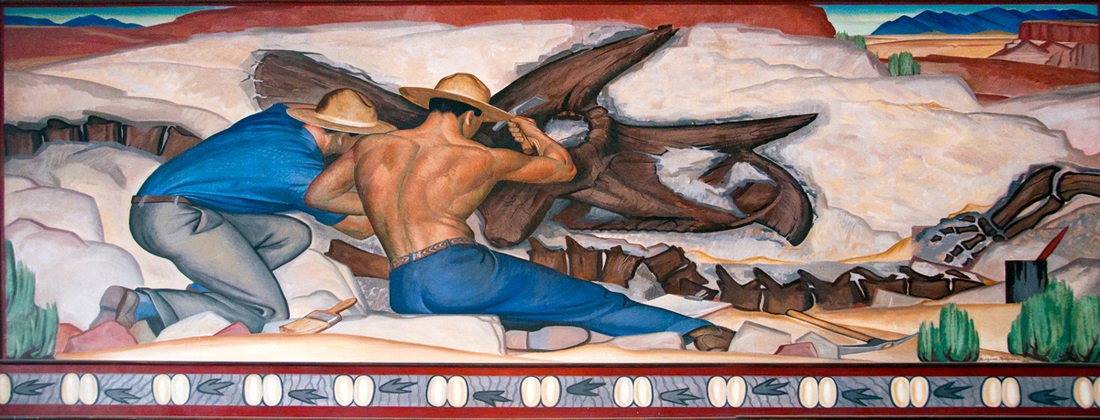

Eugene Kingman, Excavation, 1938. This mural, located in the Kemmerer Post Office, portrays the excavation of fossils in the area, and is part of a series in the lobby that makes connections between prehistoric life and modern life and work. This display also includes a border (bottom here) across the entire wall depicting dinosaur footprints and also a cross section of landforms of North America. Used with the permission of the United States Postal Service®. All rights reserved. Photo: Michael Cassity, 2011.

The Transformation of the Depression and Federal Projects to Fight Unemployment and Build a Modern Social and Economic Infrastructure

The years of the Great Depression, 1929-1943, saw a transformation of Wyoming in many ways. The federal projects that put unemployed people to work also built up the highways and streets, the dams and irrigation systems big and small, the parks and hatcheries, the courthouses and post offices, the armories and libraries, the artworks and schools, the university and the power plants, the ranger stations and the national parks, the outhouses and the hospitals, and so much more. In addition to the physical construction, however, the changes also created a larger system of social and economic connections and relationships characteristic of what is considered, technically and theoretically, "modernization." This larger system was organizational and conceptual, and that organization was increasingly that of industry with its specialization, synchronization, and centralization of relationships. It is important to note that this all evolved, that to understand, for example, New Deal programs in 1933 or 1935 is not the same as understanding those programs in 1937 or 1939--or 1943. Too often it is assumed that these programs and their projects were static and to associate a particular building or structure with a certain program is sufficient to understand it. One of my key points is that those programs changed during these years and they took on different purposes with different assumptions and goals at different times. This study, again, was one prepared for the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. Both the book, Building Up Wyoming: Depression-Era Federal Projects in Wyoming 1929-1943 and the accompanying evaluation guide (for helping to determine the historical significance of buildings and structures within the National Register system) can be downloaded at the page this link leads to.

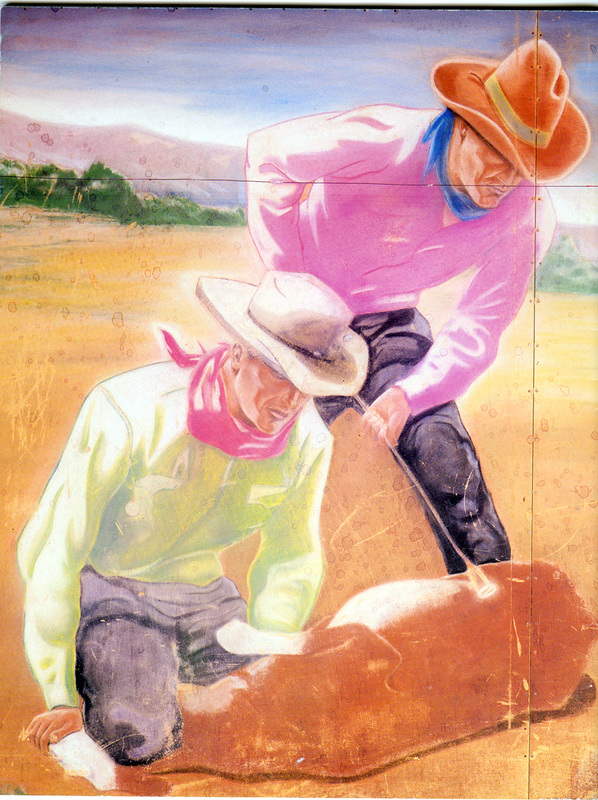

This Wyoming themed mural (Panel 16) from the walls of the enlisted service members’ club at Casper Air Base evokes New Deal art programs in subject and style and also reflects the continuity with those programs and World War II in Wyoming. Notice the seams and tacks in the wall. Photo: Michael Cassity, 2001.

World War II and the Transformation of Wyoming

In some ways, World War II

represented a continuation of the programs, or more correctly, the operating

assumptions and organizational emphasis, of key parts of the New Deal.

World War II, the economic and social changes associated with it, continued the

transformation of Wyoming that had been started decades previously, again

toward a general pattern of modernization. This essay was published in The

Wyoming History Journal (as Annals of Wyoming was known in the

difficult years of the 1990s when the State of Wyoming ceased to publish a

journal and sponsor the State Historical Society of Wyoming). This link

above takes you to the publication for 1996; turn the pages until you reach the

issue for Spring 1996, the second issue at this link.

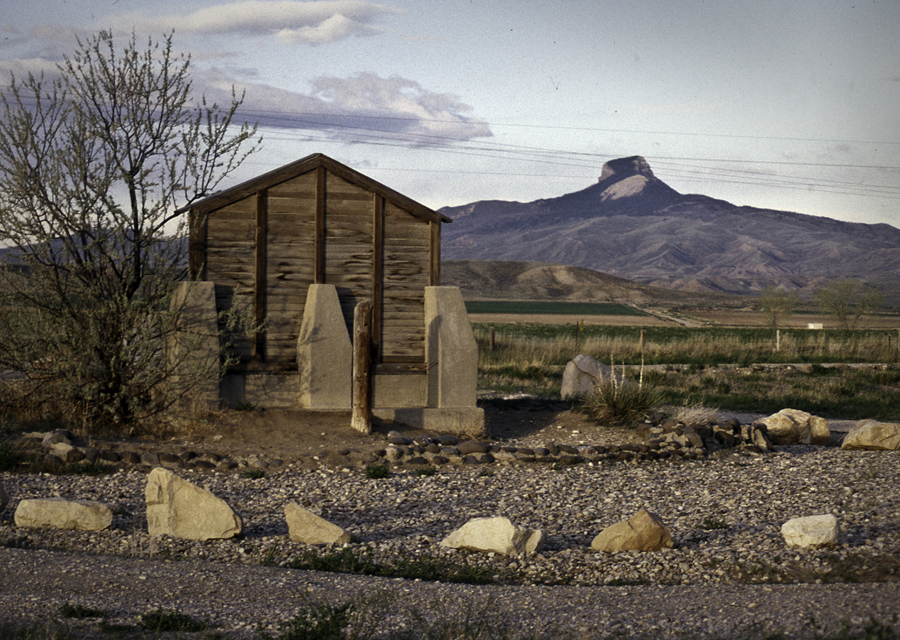

Site of Heart Mountain Relocation Center. Photo: Michael Cassity, 1990.

Heart Mountain: A Half-Century Later

In the early 1990s Wyoming and the nation reflected on the legacy of World War II in many ways, marking the sacrifices and honoring the casualties of the global war fifty years before. One observance in Wyoming brought together a special group of people, people who had been incarcerated at Heart Mountain Relocation Center because they were of Japanese heritage, even though most of them were American citizens. I attended this "reunion" and listened to the presentations and talked with many of the participants. The scars of war were still visible among these people, although many of those scars took forms that I was not prepared for. So much of the conference was about healing. The link takes you to a page containing a report I prepared for the Wyoming Council for the Humanities after the conference / reunion.

The Murie Family and the Murie Ranch near Moose: The Wilderness Movement Finds a Home in Wyoming

Sometimes loud voices suggest that any thought of environmental sensitivity and preservation of wilderness comes from people who have never been to Wyoming, but the key role of Olaus and Adolph Murie, two brilliant naturalists, and their families, suggests otherwise. Elk and moose specialists, they studied predator-prey relationships in Yellowstone and Jackson Hole and beyond and made their home at a former dude ranch near Moose. This study, which I wrote to secure the Murie Ranch as a National Historic Landmark, explores the science and the politics of the activities and associations of the Murie family. A summary page is located on this website at the link above, and the nomination itself can be found at the National Park Service link to it here.

F. E. Warren Air Force Base and the Cold War in Wyoming

This essay (at the link in the title), written in 1998 as part of a survey of historic resources on F E Warren AFB related to the Cold War, explores the changing structure and mission of the base during the Cold War, and especially how those changes (and proposed changes) shaped the relationship of the base to the city of Cheyenne--and vice versa. In that regard, it especially probes the dependence of at least one part of Wyoming on the federal government.

Main McCollister residence as it looks west to the Tetons (2000).

Paul McCollister, the Creation of Teton Village, and the Transformation of

Jackson Hole

From time to time the question arises: Why is the group of buildings that Paul W. McCollister built and lived in historically significant? That question can be answered a number of ways including how the buildings represent the settlement of Jackson Hole, a settlement process that includes not just original homesteaders and dude ranchers, but also the post-World War II proliferation of hobby ranches and tourist homes that emerged around the time that Grand Teton National Park was established in its modern form. But the answer especially has to do with the use to which the property was put by Paul McCollister. It was Paul McCollister who, at this location, in these buildings, conceived, designed, and launched the project that became Teton Village. Unlike other villages and neighborhoods around the valley like Kelly, Grovont, and Zenith, that served as community centers for farmers and ranchers who made their homes and livings nearby, Teton Village was designed as a place to attract and accommodate tourists—specifically skiers. And the creation and growth of Teton Village completely transformed the entire valley of Jackson Hole. You may love the change that Teton Village generated or you may think of it as marking a terrible turning point in the history of the valley. Either way, you can trace the beginnings of that change to these buildings overlooking Antelope Flats.

Click here to read a fuller statement of the historical significance of the buildings in the National Register nomination for the site that I prepared in 2000.

Click here to read a fuller statement of the historical significance of the buildings in the National Register nomination for the site that I prepared in 2000.

A University Campus Evolves in the Twentieth Century: The University of Wyoming in Laramie

This discussion traces the physical development of the UW campus from the construction of Old Main in 1886-1887 to the expansion eastward in the early twenty-first century. While the focus is on the physical development of the campus, hopefully a close reading will reveal more of the social, economic, and intellectual contours of the university's journey over the last 130 years. My Historic Overview is part of a historic preservation plan developed in collaboration with architectural firm The Design Studio, Inc., of Cheyenne, Wyoming and Heritage Strategies, of Sugarloaf, Pennsylvania. The version posted here is a draft and will be replaced with the final version when it is ready. The object of the effort is to help the university preserve its historic physical features.

Elsewhere in the Preservation Plan, I wrote the following to suggest some general guidelines for assessing historical significance of buildings, structures, landscapes, and other objects on the university campus. I would urge anyone interested in the university, and in the growth and preservation of the campus, to read the larger Preservation Plan document when it is posted.

Some university historical resources bear a historical significance other than, or in addition to, their architectural significance within the framework of the National Register of Historic Places. Buildings, structures, and other historical resources need to be evaluated for significance deriving from their associations with historical patterns and events that are important at the local, state, or national level. Whether or not they hold significance for their architecture, they may instead or also be significant for historical associations that are independent of their design, materials, and placement. Put simply, the institutional and academic and social contours of history on campus are vital to understanding the significance of the buildings and other features that dot the campus landscape. As we seek to understand the significance of the buildings on campus, we need, in other words, to explore the reasons for the construction of the buildings, what happened inside the buildings, and what happened around them. Ultimately, it is those activities that constitute what the university is all about.

The events and patterns of history associated with the University of Wyoming generally have to do with the distinctive purpose of the university, what sets it apart from other institutions in society. The way the university operates and the purposes to which it has set itself include several elements that contribute to the historical significance of the campus buildings and other structures. (1) The university is not just a set of buildings where a body of knowledge is passed from one generation to the next or where a workforce is trained. The university campus is designed as a place where intellectual growth can take place, where ideas can be freely discussed and explored, where the spirit of creativity can flourish, where citizens and leaders in the state and nation acquire not only information and skills but also inspiration, where students and faculty can join in a quest for deeper meanings and purposes, and where the circumstances of existence can be either reinforced or challenged by research, teaching, performance, and service. There may be times when the University fulfills that promise, and there may be times when it falls short. Both are equally significant in understanding the significance of the development of the University over time. (2) The evolution of the University of Wyoming from its beginnings in 1886 and 1887 has followed a sometimes winding path according to the strength of various forces at different times and in concert or in opposition to larger currents at work in society. For while the university is sometimes viewed as isolated from “real life,” as an ivory tower apart from the storms and stresses of life in the rest of the state and nation, university purposes, missions, organization, and issues are shaped by the larger world of which they are a part and they also help shape that world. At its most fundamental level, the size, programs, and policies of the university are closely connected to the economic, social, and cultural currents at work in the state and nation, and these are reflected in the buildings of the campus of the university. (3) Finally, the university, and its culture and institutions, is also a place where a measurable percentage of the population of the state make their homes and lives, make a living, develop relationships and values, govern themselves, entertain themselves, help each other, and in a multitude of ways create a distinct community. The buildings and structures and other resources on the campus reflect the contours of how that community has changed over time.

In buildings large or small, architecturally notable or not, the institutional, intellectual, and social activities associated with the various buildings and structures and other objects can make those resources historically significant under the framework for evaluation used by the National Register of Historic Places. The patterns of history with which these changes are associated are patterns not just of growth and expansion, but are more meaningful patterns of evolving purpose and structure. By recognizing the historical contexts from which these buildings and structures emerged, and the patterns and contexts which they also thereby reflect, moreover, we can not only learn more about the buildings; we can just as importantly learn more about the past from the buildings.

Elsewhere in the Preservation Plan, I wrote the following to suggest some general guidelines for assessing historical significance of buildings, structures, landscapes, and other objects on the university campus. I would urge anyone interested in the university, and in the growth and preservation of the campus, to read the larger Preservation Plan document when it is posted.

Some university historical resources bear a historical significance other than, or in addition to, their architectural significance within the framework of the National Register of Historic Places. Buildings, structures, and other historical resources need to be evaluated for significance deriving from their associations with historical patterns and events that are important at the local, state, or national level. Whether or not they hold significance for their architecture, they may instead or also be significant for historical associations that are independent of their design, materials, and placement. Put simply, the institutional and academic and social contours of history on campus are vital to understanding the significance of the buildings and other features that dot the campus landscape. As we seek to understand the significance of the buildings on campus, we need, in other words, to explore the reasons for the construction of the buildings, what happened inside the buildings, and what happened around them. Ultimately, it is those activities that constitute what the university is all about.

The events and patterns of history associated with the University of Wyoming generally have to do with the distinctive purpose of the university, what sets it apart from other institutions in society. The way the university operates and the purposes to which it has set itself include several elements that contribute to the historical significance of the campus buildings and other structures. (1) The university is not just a set of buildings where a body of knowledge is passed from one generation to the next or where a workforce is trained. The university campus is designed as a place where intellectual growth can take place, where ideas can be freely discussed and explored, where the spirit of creativity can flourish, where citizens and leaders in the state and nation acquire not only information and skills but also inspiration, where students and faculty can join in a quest for deeper meanings and purposes, and where the circumstances of existence can be either reinforced or challenged by research, teaching, performance, and service. There may be times when the University fulfills that promise, and there may be times when it falls short. Both are equally significant in understanding the significance of the development of the University over time. (2) The evolution of the University of Wyoming from its beginnings in 1886 and 1887 has followed a sometimes winding path according to the strength of various forces at different times and in concert or in opposition to larger currents at work in society. For while the university is sometimes viewed as isolated from “real life,” as an ivory tower apart from the storms and stresses of life in the rest of the state and nation, university purposes, missions, organization, and issues are shaped by the larger world of which they are a part and they also help shape that world. At its most fundamental level, the size, programs, and policies of the university are closely connected to the economic, social, and cultural currents at work in the state and nation, and these are reflected in the buildings of the campus of the university. (3) Finally, the university, and its culture and institutions, is also a place where a measurable percentage of the population of the state make their homes and lives, make a living, develop relationships and values, govern themselves, entertain themselves, help each other, and in a multitude of ways create a distinct community. The buildings and structures and other resources on the campus reflect the contours of how that community has changed over time.

In buildings large or small, architecturally notable or not, the institutional, intellectual, and social activities associated with the various buildings and structures and other objects can make those resources historically significant under the framework for evaluation used by the National Register of Historic Places. The patterns of history with which these changes are associated are patterns not just of growth and expansion, but are more meaningful patterns of evolving purpose and structure. By recognizing the historical contexts from which these buildings and structures emerged, and the patterns and contexts which they also thereby reflect, moreover, we can not only learn more about the buildings; we can just as importantly learn more about the past from the buildings.