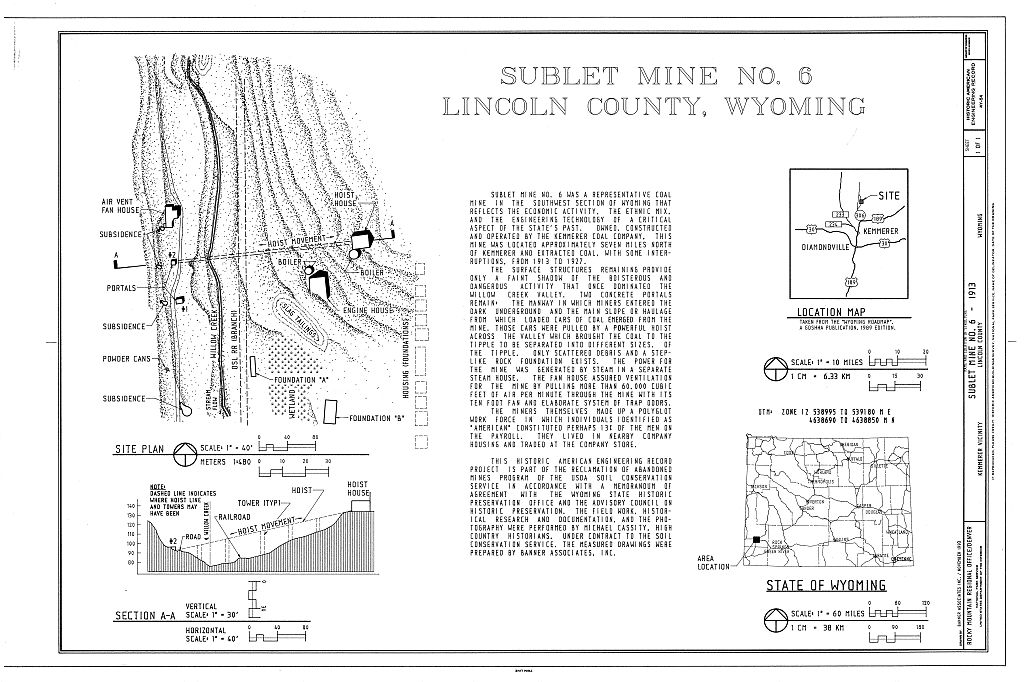

HAER / HABS Documentation:

Sublet Mine No. 6, Lincoln County, Wyoming

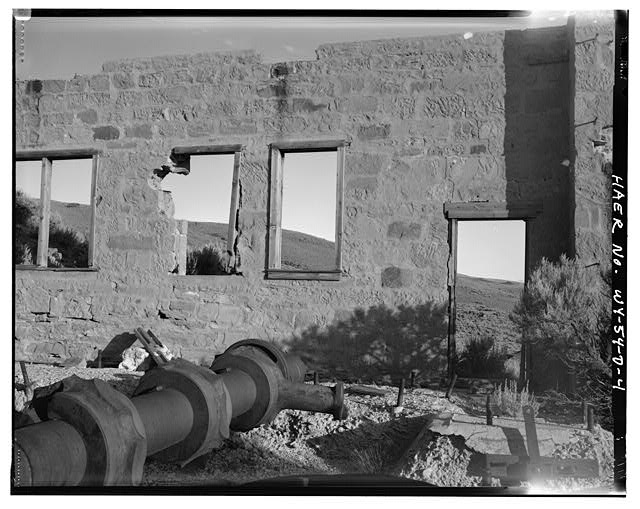

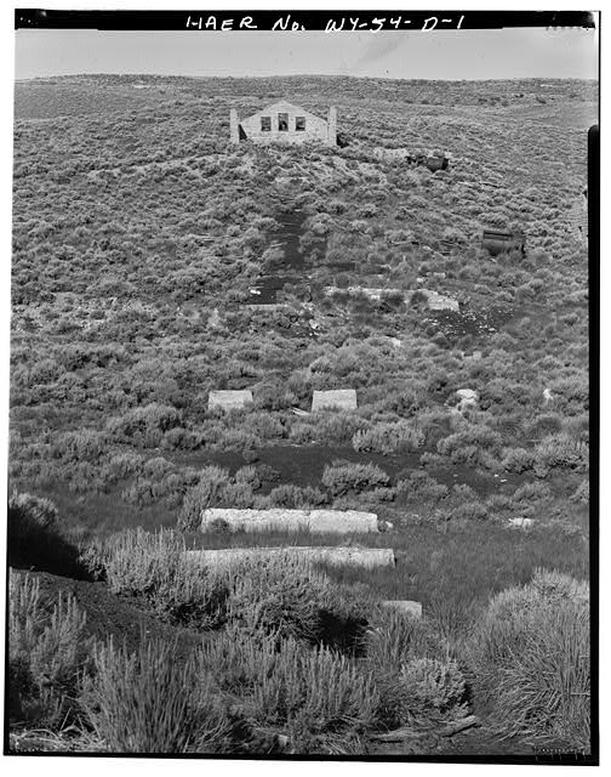

The hoist house performed a critical function within the complex by pulling the coal cars from the mine to the tipple. // Constructed of cut stone and concrete, three walls remain, as does the spindle that held the cable. Constructed in 1913 as an integral part of the Sublet Mine No. 6, built, operated, and owned by Kemmerer Coal Company; ceased production in 1927.

The Historic American Engineering Record (alongside its companion Historic American Buildings Survey and also the newer Historic American Landscape Survey) provides for documentation--history, description, drawings, maps--of significant historic features, albeit features that are too often about to vanish. This is not your average historic site or documentation (OK, what is?) and it requires careful attention, meticulous research, and close adherence to program standards (and careful coordination with National Park Service authorities). It also requires careful photography, using a 4"x5" camera to capture the details in black and white. Upon completion, the report, the photograph prints, and the negatives are all archived in the Library of Congress. Fortunately, they are now accessible on the internet, and the copies that follow (and links to them) are to the Library of Congress.

While it is clear that the initiation of this designation and documentation generally has to do with the imminent demise of the physical features, it follows from that circumstance that documentation must be complete and accurate. Since the features will soon be gone, this is the last chance to get it right.

This research and documentation was sponsored by a cooperative endeavor of the USDA Soil Conservation Service, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, and US Department of the Interior, National Park Service in anticipation of the "reclamation" of the land on which the mine was located.

If you think that a mine is just a hole in the ground, think again. There is (was) an elaborate infrastructure of buildings, structures, and other features above ground that kept the mine going. There were the mine entrances, adits that opened into the side of a hill with their tunnels (mines) following the seam of coal into the bowels of the earth. There were the engines that operated huge hoists that pulled (after mechanization replaced the mules) cars of coal up out of the mines. There were the enormous fans that pulled air through the tunnels, providing ventilation for the miners. There were the tipples at which the coal was sorted. There were the administrative buildings. There were the residential buildings. There were the powder houses for the dynamite. There were the workers' houses. There were the stores where the workers and their families purchased the necessities of life. The mines operated under the ground, deep in the earth, but they also operated above the ground, much like a factory.

Thus there were a number of physical features at work in the coal mines. Plus, there were other forces at work. At Sublet Mine No. 6, north of Kemmerer, Wyoming, the forces of the market reached not just down under ground but across the seas. A global market in labor brought workers to this mine from distant quarters. The workers who built and mined the coal at Sublet No. 6 were immigrants. Quoting from my HAER documentation:

The most striking feature of the work force at Sublet No. 6 was its ethnicity. This polyglot force was noted even by the mine inspector in his 1915 report when he commented that the majority of mine workers in the district were foreigners who did not understand English.[1] Sublet Mine No. 6 was reflective of this diverse ethnic work force. In the Kemmerer Coal Company collection of documents in the Historical Research Division of the Wyoming Department of Commerce is an undated list of employees of Sublet Mine No. 6 that divides them into nationality groups. Of the 112 workers named, those identified as “Americans” total fourteen. The largest groups were those from Italy (twenty-nine) and those from Japan (twenty-three). After that Austrian (nineteen) and Polish (twelve) workers were followed by workers from Finland (four), Spain (four), Syria (three), Germany (one), Mexico (one), Montenegro (one), and Russia (one).[2] A comparison of the names on this list with other names associated with the mine is inconclusive, but the list had to have been prepared prior to 1920.

In the powder house explosion and fire of 1920, there is another sampling of the work force. The eight victims of that accident included two Italians, one German, one Austrian, one “Polish American,” one Korean, one Japanese, and one “Finlander.” The closest person to being identified as “American,” as in the employment list above, was Matt Wisniewski, the “Polish American.”[3] Aside from the fact that these workers in the mines could likely not talk much with each other because of language differences, the safety implications of the language barriers were substantial. Nonetheless, there often appeared to be a commonality of culture at least in its exchange as different groups celebrated different holidays, inviting the others to the occasion. There is, however, an obvious omission from this list of ethnic groups. When asked if there were any black workers in the company, William Harris responded: “Had one. That’s the only one I remember and he lived up here [in Frontier].”[4]

Then, consider this, also from my HAER submission:

The next most salient fact of life in the mines, was the danger. Accidents were routine. Fatal accidents were not uncommon. Death from the explosion of a shot that had not detonated before the miner returned to the workface, from the fall of rock, from the fall of coal either from the roof or from the work face, from falling under the string of coal cars (called a trip), from being thrown from the tipple, and from an explosion at the powder house all claimed lives in the course of work at Sublet Mine No. 6. The following fatalities can be documented from the annual mine inspector published reports:

- July 30, 1914: Charles Nickols, American, fifty-four, married, with two children. Nickols died while raising a chute at No. 6 tipple; the chute caught the timber upon which Nickols was standing, the rope holding the timber broke, and Nickols was thrown twenty-nine feet to the ground, striking his head on the railroad track below.[5]

- September 28, 1915: Paul Bertie, Austrian, forty-six years old, and married. He and his partner had drilled, loaded, and lit the fuse and gone on to the entry to await the explosion. Although they thought they heard the shot explode and returned to work at the face of the coal, the shot went off after they returned, killing Bertie.[6]

- December 5, 1915: William Hendrickson, Finlander, forty-five years old, with wife and one child. Although his room was well timbered with props, “he was making place to set two more props when the rock fell, killing him.”[7]

- November 23, 1916: Theo. Crise, Italian, thirty-six years old, single. While working in a room, he lit the fuse to his shot and went onto the entry. After waiting and hearing a shot explode he returned to his room when his own shot exploded, injuring him so that he died November 30, 1916.[8]

- January 10, 1917: S. Munesada, Japanese, forty-five years old, married with two children. Rock fell on him, killing him.[9]

- March 20, 1917: Ossi Anderson, Finlander, twenty-four years old, single. Anderson was a rope-rider, the individual who rode the hoist cable pulling the cars into and out of the mine, and who controlled the trips. Anderson was moving from the fourth entry to the third on the trip with the intention of jumping off at the third entry. Somehow he jumped early, seventy-five feet below the third entry and fell back under the trip.[10]

- June 30, 1917: Philip Torgosh, Polish, fifty-three years old, with a wife and one child. Torgosh and his partner mistook another shot for theirs and returned to their room and Torgosh was at the working face when the shot exploded, killing him.[11]

- March 6, 1918: Dom Penolio, Italian, forty years old, single. Penolio was a shot inspector who was setting a prop to hang some brattice--the canvas that would help direct the flow of air--near the face of an entry when a large rock fell. Ordinarily one could “sound” the rock with a tap on the roof to tell if the roof was loose; “the rock was of such size that it was impossible to sound to determine whether or not same was safe.”[12]

- November 23, 1918: Mike Polirio, Mexican, forty-one years old. He started to drill a hole in some top coal which was loose; the coal separated and fell on him. Polirio died December 8, 1918.[13]

- February 28, 1919: John Goun, Japanese, forty-six years old, single. While crossing his room chute he slipped and fell into the chute and hit a prop he had placed across the chute to catch or hold coal, hitting his stomach severely. He died March 3, 1919.[14]

- May 29, 1920: Thomas Boam, English, with a wife and one child under sixteen years. He and his son were working as partners in a room and had fired a shot the previous evening. The coal had been loosened, but still adhered to the working face. When the senior Boam tried to loosen the coal and pull it down, it fell over on him, killing him. The piece of coal was estimated to weigh 1200 pounds.[15]

July 26, 1920:

- B. M. Shin, Korean, thirty-seven years old, single;

- Nomini Robert, Italian, thirty-five years old, single;

- Matt Wisniewski, Polish American, eighteen years old, single;

- F. G. Kempfenkel, German thirty-one years old, wife and 3 children under 16 years;

- Steve Weber, Austrian, fifty-two years old, married (wife living in Austria);

- John Perolio, Italian, thirty-four years old, single;

- T. Emagawa, Japanese, thirty-three years old, single;

- Alfred Noukki, Finlander, forty-three years old, single.

These eight men were killed in a single explosion at the powder house, located “a considerable distance south of the mine.” “The miners, on returning to the surface at quitting time, take their empty powder bottles to the magazine, have them filled by a man employed for that purpose and then return to the mine mouth with loaded bottles and deposit them in a powder box, from which place the Company delivers them to their respective owners in the mine. It was while the eight men in question were standing at the powder magazine door awaiting to have their cans filled that the explosion took place . . . .” The conclusion of the investigation into the explosion was that a spark ignited the powder when a wooden mallet or hammer was used to puncture the top of the powder keg.[16]

February 20, 1923: T. Hashimoto, forty-five years old, married with one child under sixteen years. Killed by fall of coal.[17]

January 6, 1926: Joe Kusmirik, unspecified age and family status. Killed by fall of coal; shot had failed to bring down a piece about eighteen inches thick until he was under it.[18]

These twenty-one men died in a mine that operated around thirteen years. Nine of them died on the surface of the mine and the others in the haulage or entries and rooms. As if the deaths in this one mine were not grim enough reminder of the dangers of the technology and operation, news of accidents in neighboring mines provided reinforcement. On September 16, 1924, thirty-nine miners died in a gas explosion in nearby Sublet Mine No. 5.[19] The long term consequences of non-fatal accidents and of diseases incurred in the mine can not be calculated.

* * * *

The study of this mine thus represents an important opportunity and an important mandate to explore the intersection of technology, ethnicity, property relations, markets, and more. It represents an opportunity thereby to explore the roots of the world we live in today.

By the early years of the 1920s the mine was fading, production was diminishing and the future darkened. I summarize the study, and the mine, in this way:

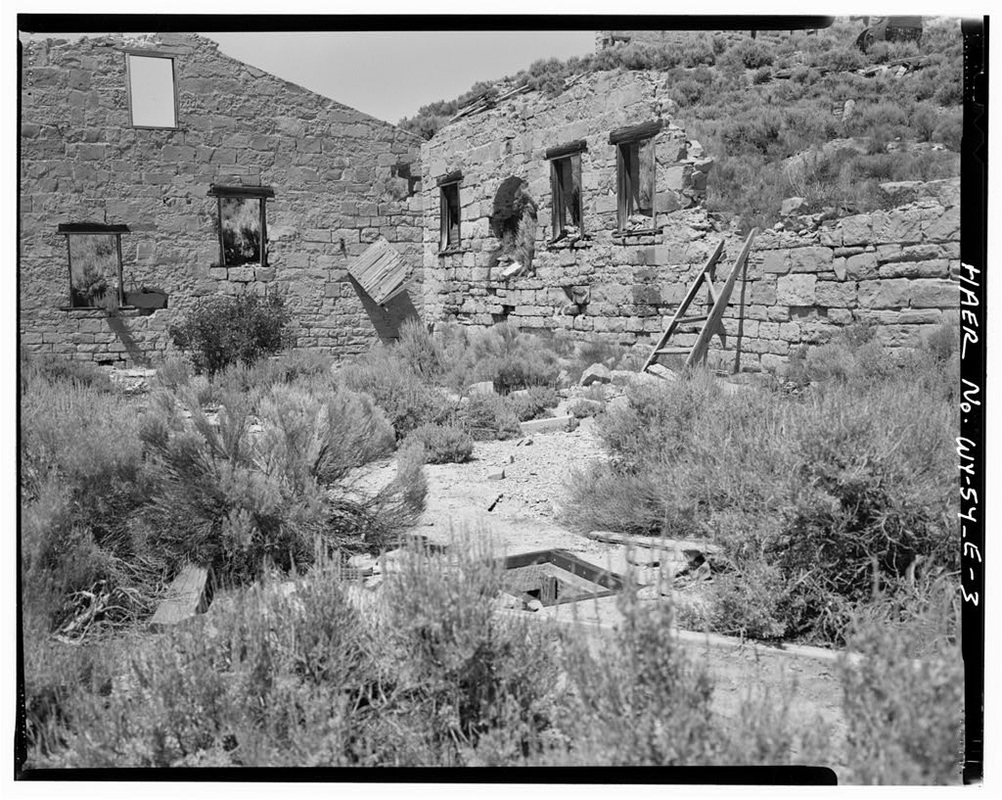

During the 1920s coal mining in Wyoming suffered from the results of an unstable market and at the same time had endeavored to modernize its equipment to cut labor costs. Sublet Mine No. 6 demonstrates this pattern, but because of the depletion of accessible coal and the decline in prices it could not continue. Most of its equipment was dismantled and moved to other sites. Virtually nothing is left of the tipple and its footprint is hard to detect. The housing has disappeared except for foundation remnants in one row (see photos HAER No. WY-54-H to WY-54-N). The fan house still demonstrates the careful workmanship in the stone walls that would direct and regulate the flow of air pulled through the mine (see photo HAER No. WY-54-C-7). The Stevens ten foot fan rests on a small brace, long since having turned its last revolution (see photo HAER No. WY-54-C-3). The massive steel doors in the building, also to regulate the flow of air, remain. One door lifts vertically on hinges (see photo HAER No. WY-54-C-5) while the others open and close to left and right (see photo HAER No. WY-54-C-6). The two boilers from the engine house are removed and lay disheveled above and beside the stone walls on three sides of the engine house. One foundation with windows still holding bars for security could have been the company store, but this is speculative (see photo HAER No. WY-54-G-1; HAER No. WY-54-G-2). To the south of the site a slab of concrete, sometimes said to have been the roof of the powder house that exploded in 1920, lies on the ground. Of the portals, the manway--the entrance to the south--is crumbling (see photo HAER No. WY-54-A-1). All slopes are sealed by cave-ins. The defining remnants of the entire site can quickly be appreciated from two critical perspectives. The main slope still bears the name of the mine on its arch at the portal, “No. 6 1913,” (see photo HAER No. WY-54-B-2) although vandals have done their best to remove the letters and numbers. From that portal, the view of the eastern side of the valley becomes comprehensible as the hoist house rises prominently ahead and as other foundations fit into place. Directly across the valley and above the site stand three walls of the hoist house like a cathedral dominating the valley (see photo HAER No. WY-54-D-1). Indeed, the view of the site from the hoist house, especially straight across to the slope that used to release the coal from the mine’s grid of subterranean rooms and entries and haulages (see photo HAER No. WY-54-2), is a view that captures most of what remains of Sublet Mine No. 6. And what remains is a reminder of a vibrant but remote period of economic growth and decline, of technology and mechanical power, of the socially powerful and the powerless, of worlds of light and darkness, of diverse populations mixing and laboring, of deep tragedy and sorrow, and of dreams, disappointments, and hardships.

Of course, "what remains" of the mine in 1993 would not remain long. Actually, all that remains now is the HAER documentation. And memories. And lessons learned.

[1]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1915, 5. Also cf. Gardner, Forgotten Frontier, who discusses ethnicity in the coal mines and towns as a recurrent theme of mining in Wyoming.

[2]Undated “List of Men on Pay Roll (Subdivided as to Nativity,)” H86-13, Kemmerer Coal Company Collection, Wyoming Department of Commerce, Historical Research Collections Division, Cheyenne.

[3]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1920, 41.

[4]Gardner and Rosenberg, Interview with William Harris, 207.

[5]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1914, 16.

[6]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1915, 13.

[7]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1916, 26.

[8]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1916, 13.

[9]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1917, 15.

[10]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1917, 18.

[11]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1917, 22.

[12]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1918, 31.

[13]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1918, 31.

[14]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1919, 32.

[15]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1920, 39.

[16]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1920, 5-6, 41.

[17]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1923, 21.

[18]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1926, 32.

[19]Annual Report of the State Coal Mine Inspector, State of Wyoming, 1924, 18-22; see also the account in Lorenzo Groutage, Wyoming Mine Run (Salt Lake City, 1981), 71-89.

The fan house performed a critical function within the complex by providing ventilation to the underground mine workers. // Constructed of cut stone and concrete in its lower level with brick walls above, the lower level was divided into air passageways with doors to regulate the flow of air; contains 10 ft. Stevens fan.