A Wyoming Trilogy (of sorts) . . . and more

Although neither dramatic nor literary, and thus perhaps not technically forming a “real” trilogy, these three volumes in the history of Wyoming are united by a common focus and they span the bulk of the history of the area that became Wyoming from the first permanent settlement at Fort Laramie to the decade and a half following World War II. Plus, the volumes overlap and that congruence hopefully provides further connection. The idea here is that, considered together, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts and that the analysis presented in the combination of the three books provides a view of Wyoming history that goes beyond any of the three individual volumes.

So I present them together and make them available to be read and downloaded together. The truth is, they are best considered as parts of a coherent understanding of Wyoming history rather than as separate fragments of that past.

So I present them together and make them available to be read and downloaded together. The truth is, they are best considered as parts of a coherent understanding of Wyoming history rather than as separate fragments of that past.

The Perspective of the Trilogy

It is sometimes said that fish are unaware of the water in which they swim. They swim in water and they live out their lives in water, but they are not consciously aware of it. They take it as a given. They are aware of whether they can eat something they see in the water, or if something they see is going to eat them. They are aware of other fish in the water that they need to mate with. They are aware when they don’t have water to swim in, but they really are not aware of the water. They take it for granted.

By the same token, it is also true that many of us are often unaware of the currents of history in which we live our lives, unaware of the streams of economic, political, cultural, and social change that connect us with earlier generations of people in Wyoming and the nation.

These three books are intended to help us see the stream of history in which we live and the course of which we help shape by our daily actions. They focus on issues that help us understand where our society has been and how it has gotten to where it is today. Fort Laramie’s People: An Exploration in Historical Context examines the process of social change associated with Fort Laramie, a process that is considerably greater than the customary “forts and fights” focus of some histories. The critical element in this account is the transformation of a community based on tolerance, acceptance, decentralized authority, political and economic equality, and diverse cultures to people who are fragmented culturally and whose institutions are centralized in power, a society that tended to leave aspirations and values of many of its members aside or make of them outcasts because of their values.

Wyoming Will Be Your New Home . . .: Ranching, Farming, and Homesteading in Wyoming 1860-1960 (Cheyenne: Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office, 2011) takes a new look at Wyoming’s agricultural history, a history that in its early years offered hope for many with the promise of land to homestead, land on which they would not likely get rich but on which they could become independent and not beholden to anyone. (And don't think of this as merely farming and ranching; until 1920 the majority of Americans lived in the countryside and small villages. It's a history of all of us.) That promise attracted many settlers and Wyoming’s farms and ranches thrived modestly and increased in numbers until the 1930s. But they were encouraged to go into debt and to become dependent on markets to pay those debts, with the consequence that the Agricultural Depression of the 1920s took its toll on these previously independent peoples and the agricultural policies of the New Deal pushed more of them off the land, consolidating the land in the hands of fewer and larger commercial operators. Government policy and the forces of modernization both deepened this trend during World War II and in the decades afterwards farming and ranching in Wyoming had become of necessity often a business more than a way of life, with the families who held on to that way of life as their purpose dwindling in number, but not in determination.

Building Up Wyoming: Depression-Era Federal Projects in Wyoming, 1929-1943 (Cheyenne: Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office, 2013) examines the federal public works and work relief projects during both the Herbert Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt administrations. But it is concerned with more than just chronicling physical construction projects. Those projects were part of a larger pattern of social and economic changes that ultimately contributed to a more centralized, specialized, synchronized set of institutions and relationships with economic profit and production as goals, and those goals took on an increasingly military flavor that endured beyond the militarization of Keynesian economics during World War II even when the instigators and planners were from the private sector operating through public institutions. The book questions whether the changes in society produced by the Depression strengthened the individual and the community or whether they built up and strengthened the institutions—public and private—that diminish the individual and community. And that is the question to ask of other developments in the economy and society, developments that included the increasing power and role of vast private institutions and the diminution of individuals in their structures and operations. Those questions go beyond particular buildings, beyond specific projects, and beyond the state of Wyoming in the Depression.

By the same token, it is also true that many of us are often unaware of the currents of history in which we live our lives, unaware of the streams of economic, political, cultural, and social change that connect us with earlier generations of people in Wyoming and the nation.

These three books are intended to help us see the stream of history in which we live and the course of which we help shape by our daily actions. They focus on issues that help us understand where our society has been and how it has gotten to where it is today. Fort Laramie’s People: An Exploration in Historical Context examines the process of social change associated with Fort Laramie, a process that is considerably greater than the customary “forts and fights” focus of some histories. The critical element in this account is the transformation of a community based on tolerance, acceptance, decentralized authority, political and economic equality, and diverse cultures to people who are fragmented culturally and whose institutions are centralized in power, a society that tended to leave aspirations and values of many of its members aside or make of them outcasts because of their values.

Wyoming Will Be Your New Home . . .: Ranching, Farming, and Homesteading in Wyoming 1860-1960 (Cheyenne: Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office, 2011) takes a new look at Wyoming’s agricultural history, a history that in its early years offered hope for many with the promise of land to homestead, land on which they would not likely get rich but on which they could become independent and not beholden to anyone. (And don't think of this as merely farming and ranching; until 1920 the majority of Americans lived in the countryside and small villages. It's a history of all of us.) That promise attracted many settlers and Wyoming’s farms and ranches thrived modestly and increased in numbers until the 1930s. But they were encouraged to go into debt and to become dependent on markets to pay those debts, with the consequence that the Agricultural Depression of the 1920s took its toll on these previously independent peoples and the agricultural policies of the New Deal pushed more of them off the land, consolidating the land in the hands of fewer and larger commercial operators. Government policy and the forces of modernization both deepened this trend during World War II and in the decades afterwards farming and ranching in Wyoming had become of necessity often a business more than a way of life, with the families who held on to that way of life as their purpose dwindling in number, but not in determination.

Building Up Wyoming: Depression-Era Federal Projects in Wyoming, 1929-1943 (Cheyenne: Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office, 2013) examines the federal public works and work relief projects during both the Herbert Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt administrations. But it is concerned with more than just chronicling physical construction projects. Those projects were part of a larger pattern of social and economic changes that ultimately contributed to a more centralized, specialized, synchronized set of institutions and relationships with economic profit and production as goals, and those goals took on an increasingly military flavor that endured beyond the militarization of Keynesian economics during World War II even when the instigators and planners were from the private sector operating through public institutions. The book questions whether the changes in society produced by the Depression strengthened the individual and the community or whether they built up and strengthened the institutions—public and private—that diminish the individual and community. And that is the question to ask of other developments in the economy and society, developments that included the increasing power and role of vast private institutions and the diminution of individuals in their structures and operations. Those questions go beyond particular buildings, beyond specific projects, and beyond the state of Wyoming in the Depression.

Nota Bene: Beyond Wyoming

It is important to note that the issues and the course of history examined in this trilogy are not restricted to within the borders of Wyoming. The issues are larger than the political or geographic organization of historical discussion sometimes allows. In fact, a central point, even a leitmotiv, of the trilogy is that the issues and experiences considered reach well beyond Wyoming in their origins, in their experience, and in their consequences. They are often national or even universal in comprehension. You don't have to be from or live in Wyoming to make sense of what is discussed in these books.

A Note of Gratitude

I want to thank the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office, and especially Mary Hopkins, the State Historic Preservation Officer, and Judy Wolf, the Chief, Historic Context Planning and Development Program, for their terrific support and encouragement as I developed the homesteading book and the Depression-era federal projects book as historic contexts for their program. Judy Wolf in particular has been a constant and frequent source of assistance and perspective as I have worked on these projects. I hope the people of Wyoming appreciate the tremendous service these people, and this office, provide. Visit their website at this link.

Beyond the Trilogy

I have supplemented the general inquiry undertaken in the trilogy with multiple shorter essays. Written for different purposes (some as articles, some as National Register nominations, one as a National Historic Landmark nomination, one as documentation for the Historic American Engineering Record, some as personal reflections, and more), they still come back to the same set of problems as those addressed in the trilogy: the way Wyoming’s economy and society have transformed and how that transformation has reshaped the circumstances of life for Wyoming’s various peoples.

Wyoming history consists largely of a continuous transformation in the way people have lived and worked, made their livings, raised their children, looked to the future, and found purpose and meaning in each day’s labors. At one level, it has been a transformation from isolated lives (whether lonely or fulfilling) and communities (whether villages or neighborhoods or actual cities) to lives that are increasingly connected to those of others across the county, across the state, across the nation. On another level it has been a transformation from living a life of relative autonomy, dependent upon individual talents and strengths and the variables of family and weather and the circumstances of landholding, to living a life increasingly dependent upon vast impersonal markets and the decisions of others elsewhere. How beneficial that transformation has been depends largely on one’s view of the proper role of the individual and of the public in the larger economy, the very purpose of organized society, and, in fact, the fundamental question of the nature of the human condition. For my part, I attempt to explore those issues in these essays, sometimes explicitly and sometimes only by implication. To undertake that exploration is not just an opportunity of the historian; it is a fundamental responsibility of the historian. It is why we study history.

The Lives of Coal Miners in Wyoming

in the Early Twentieth Century:

The Case of Sublet Mine No. 6

Before strip mining became the dominant system of coal production in Wyoming, underground mines that extracted the coal from its seams, carried it to the surface, and loaded it into railroad cars defined the lives and work of people from a multitude of cultures. This essay (at the link above in the title) looks at the development, the technology, the life and labor, and the decline of one mine, a mine that operated north of Kemmerer from 1913 to 1927.

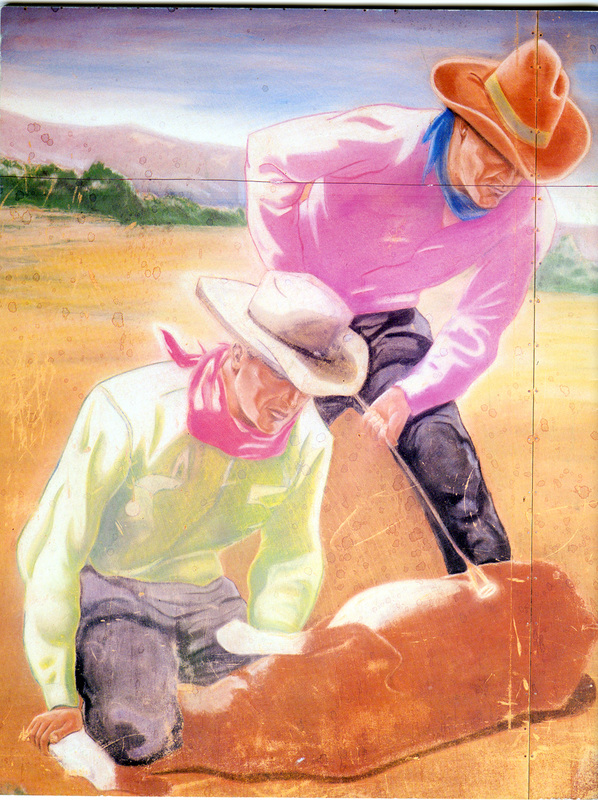

This Wyoming-themed mural (Panel 16) from the walls of the enlisted service members’ club at Casper Air Base evokes New Deal art programs in subject and style and also reflects the continuity with those programs and World War II in Wyoming. Notice the seams and tacks in the wall. Photo: Michael Cassity, 2001.

World War II and the Transformation of Wyoming

In some ways, World War II represented a continuation of the programs, or more correctly, the operating assumptions and organizational emphasis, of key parts of the New Deal. World War II, the economic and social changes associated with it, continued the transformation of Wyoming that had been started decades previously, again toward a general pattern of modernization. This essay was published in The Wyoming History Journal (as Annals of Wyoming was known in the difficult years of the 1990s when the State of Wyoming ceased to publish a journal and sponsor the State Historical Society of Wyoming). This link above takes you to the publication for 1996; turn the pages until you reach the issue for Spring 1996, the second issue at this link.

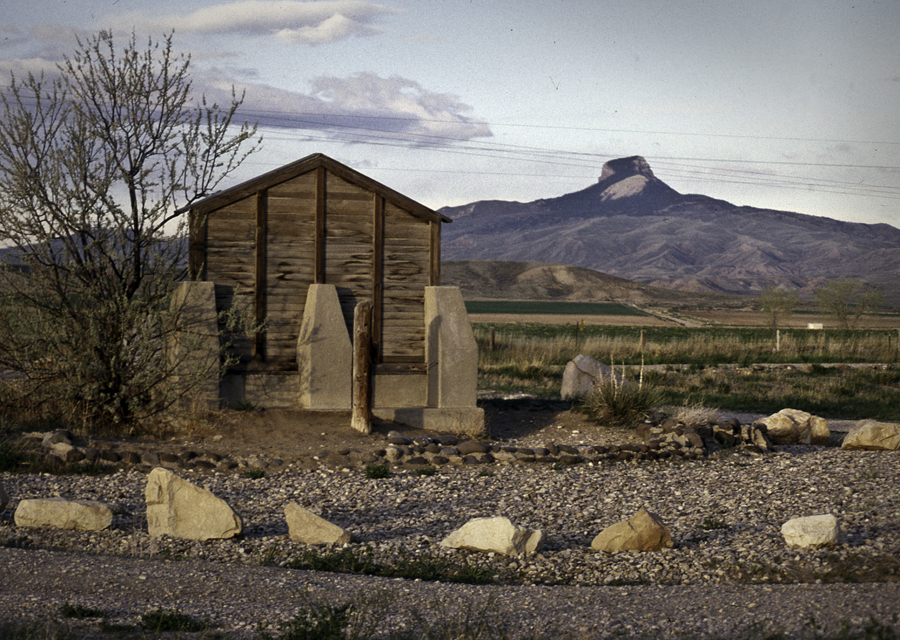

Site of Heart Mountain Relocation Center. Photo: Michael Cassity, 1990.

Heart Mountain: A Half-Century Later

In the early 1990s Wyoming and the nation reflected on the legacy of World War II in many ways, marking the sacrifices and honoring the casualties of the global war fifty years before. One observance in Wyoming brought together a special group of people, people who had been incarcerated at Heart Mountain Relocation Center because they were of Japanese heritage, even though most of them were American citizens. I attended this "reunion" and listened to the presentations and talked with many of the participants. The scars of war were still visible among these people, although many of those scars took forms that I was not prepared for. So much of the conference was about healing. The link takes you to a page containing a report I prepared for the Wyoming Council for the Humanities after the conference / reunion.

The Murie Family and the

Murie Ranch near Moose:

The Wilderness Movement Finds a Home in Wyoming

Sometimes loud voices suggest that any thought of environmental sensitivity and preservation of wilderness comes from people who have never been to Wyoming, but the key role of Olaus and Adolph Murie, two brilliant naturalists, and their families, suggests otherwise. Elk and moose specialists, they studied predator-prey relationships in Yellowstone and Jackson Hole and beyond and made their home at a former dude ranch near Moose. This study, which I wrote to secure the Murie Ranch as a National Historic Landmark, explores the science and the politics of the activities and associations of the Murie family. A summary page is located on this website at the link above, and the nomination itself can be found at the National Park Service link to it here.

F. E. Warren Air Force Base, Cheyenne, and the Cold War in Wyoming

This essay (at the link in the title), written in 1998 as part of a survey of historic resources on F E Warren AFB related to the Cold War, explores the changing structure and mission of the base during the Cold War, and especially how those changes (and proposed changes) shaped the relationship of the base to the city of Cheyenne--and vice versa. In that regard, it especially probes the dependence of at least one part of Wyoming on the federal government and implicitly explores subtle aspects of President Dwight Eisenhower's warning about a Military Industrial Complex.

McCollister home above Antelope Flats, 2000.

Paul McCollister, the Creation of Teton Village, and the Transformation of

Jackson Hole

From time to time the question arises: Why is the group of buildings that Paul W. McCollister built and lived in historically significant? That question can be answered a number of ways including how the buildings represent the settlement of Jackson Hole, a settlement process that includes not just original homesteaders and dude ranchers, but also the post-World War II proliferation of hobby ranches and tourist homes that emerged around the time that Grand Teton National Park was established in its modern form. But the answer especially has to do with the use to which the property was put by Paul McCollister. It was Paul McCollister who, at this location, in these buildings, conceived, designed, and launched the project that became Teton Village. Unlike other villages and neighborhoods around the valley like Kelly, Grovont, and Zenith, which served as community centers for farmers and ranchers who made their homes and livings nearby, Teton Village was designed as a place to attract and accommodate tourists—specifically skiers. And the creation and growth of Teton Village completely transformed the entire valley of Jackson Hole. You may love the change that Teton Village generated or you may think of it as marking a terrible turning point in the history of the valley. Either way, you can trace the beginnings of that change to these buildings overlooking Antelope Flats.

Click here to read a fuller statement of the historical significance of the buildings in the National Register nomination for the site that I prepared in 2000.

Click here to read a fuller statement of the historical significance of the buildings in the National Register nomination for the site that I prepared in 2000.

A University Campus Evolves in the Twentieth Century:

The University of Wyoming in Laramie

This discussion traces the physical development of the UW campus from the construction of Old Main in 1886-1887 to the expansion eastward in the early twenty-first century. While the focus is on the physical development of the campus, hopefully a close reading will reveal more of the social, economic, and intellectual contours of the university's journey over the last 130 years. My Historic Overview is part of a historic preservation plan developed in collaboration with architectural firm The Design Studio, Inc., of Cheyenne, Wyoming and Heritage Strategies, of Sugarloaf, Pennsylvania. The version posted here is a draft and will be replaced with the final version when it is ready. The object of the effort is to help the university preserve its historic physical features.

Elsewhere in the Preservation Plan, I wrote the following to suggest some general guidelines for assessing historical significance of buildings, structures, landscapes, and other objects on the university campus. I would urge anyone interested in the university, and in the growth and preservation of the campus, to read the larger Preservation Plan document when it is posted.

Some university historical resources bear a historical significance other than, or in addition to, their architectural significance within the framework of the National Register of Historic Places. Buildings, structures, and other historical resources need to be evaluated for significance deriving from their associations with historical patterns and events that are important at the local, state, or national level. Whether or not they hold significance for their architecture, they may instead or also be significant for historical associations that are independent of their design, materials, and placement. Put simply, the institutional and academic and social contours of history on campus are vital to understanding the significance of the buildings and other features that dot the campus landscape. As we seek to understand the significance of the buildings on campus, we need, in other words, to explore the reasons for the construction of the buildings, what happened inside the buildings, and what happened around them. Ultimately, it is those activities that constitute what the university is all about.

The events and patterns of history associated with the University of Wyoming generally have to do with the distinctive purpose of the university, what sets it apart from other institutions in society. The way the university operates and the purposes to which it has set itself include several elements that contribute to the historical significance of the campus buildings and other structures. (1) The university is not just a set of buildings where a body of knowledge is passed from one generation to the next or where a workforce is trained. The university campus is designed as a place where intellectual growth can take place, where ideas can be freely discussed and explored, where the spirit of creativity can flourish, where citizens and leaders in the state and nation acquire not only information and skills but also inspiration, where students and faculty can join in a quest for deeper meanings and purposes, and where the circumstances of existence can be either reinforced or challenged by research, teaching, performance, and service. There may be times when the University fulfills that promise, and there may be times when it falls short. Both are equally significant in understanding the significance of the development of the University over time. (2) The evolution of the University of Wyoming from its beginnings in 1886 and 1887 has followed a sometimes winding path according to the strength of various forces at different times and in concert or in opposition to larger currents at work in society. For while the university is sometimes viewed as isolated from “real life,” as an ivory tower apart from the storms and stresses of life in the rest of the state and nation, university purposes, missions, organization, and issues are shaped by the larger world of which they are a part and they also help shape that world. At its most fundamental level, the size, programs, and policies of the university are closely connected to the economic, social, and cultural currents at work in the state and nation, and these are reflected in the buildings of the campus of the university. (3) Finally, the university, and its culture and institutions, is also a place where a measurable percentage of the population of the state make their homes and lives, make a living, develop relationships and values, govern themselves, entertain themselves, help each other, and in a multitude of ways create a distinct community. The buildings and structures and other resources on the campus reflect the contours of how that community has changed over time.

In buildings large or small, architecturally notable or not, the institutional, intellectual, and social activities associated with the various buildings and structures and other objects can make those resources historically significant under the framework for evaluation used by the National Register of Historic Places. The patterns of history with which these changes are associated are patterns not just of growth and expansion, but are more meaningful patterns of evolving purpose and structure. By recognizing the historical contexts from which these buildings and structures emerged, and the patterns and contexts which they also thereby reflect, moreover, we can not only learn more about the buildings; we can just as importantly learn more about the past from the buildings.

Elsewhere in the Preservation Plan, I wrote the following to suggest some general guidelines for assessing historical significance of buildings, structures, landscapes, and other objects on the university campus. I would urge anyone interested in the university, and in the growth and preservation of the campus, to read the larger Preservation Plan document when it is posted.

Some university historical resources bear a historical significance other than, or in addition to, their architectural significance within the framework of the National Register of Historic Places. Buildings, structures, and other historical resources need to be evaluated for significance deriving from their associations with historical patterns and events that are important at the local, state, or national level. Whether or not they hold significance for their architecture, they may instead or also be significant for historical associations that are independent of their design, materials, and placement. Put simply, the institutional and academic and social contours of history on campus are vital to understanding the significance of the buildings and other features that dot the campus landscape. As we seek to understand the significance of the buildings on campus, we need, in other words, to explore the reasons for the construction of the buildings, what happened inside the buildings, and what happened around them. Ultimately, it is those activities that constitute what the university is all about.

The events and patterns of history associated with the University of Wyoming generally have to do with the distinctive purpose of the university, what sets it apart from other institutions in society. The way the university operates and the purposes to which it has set itself include several elements that contribute to the historical significance of the campus buildings and other structures. (1) The university is not just a set of buildings where a body of knowledge is passed from one generation to the next or where a workforce is trained. The university campus is designed as a place where intellectual growth can take place, where ideas can be freely discussed and explored, where the spirit of creativity can flourish, where citizens and leaders in the state and nation acquire not only information and skills but also inspiration, where students and faculty can join in a quest for deeper meanings and purposes, and where the circumstances of existence can be either reinforced or challenged by research, teaching, performance, and service. There may be times when the University fulfills that promise, and there may be times when it falls short. Both are equally significant in understanding the significance of the development of the University over time. (2) The evolution of the University of Wyoming from its beginnings in 1886 and 1887 has followed a sometimes winding path according to the strength of various forces at different times and in concert or in opposition to larger currents at work in society. For while the university is sometimes viewed as isolated from “real life,” as an ivory tower apart from the storms and stresses of life in the rest of the state and nation, university purposes, missions, organization, and issues are shaped by the larger world of which they are a part and they also help shape that world. At its most fundamental level, the size, programs, and policies of the university are closely connected to the economic, social, and cultural currents at work in the state and nation, and these are reflected in the buildings of the campus of the university. (3) Finally, the university, and its culture and institutions, is also a place where a measurable percentage of the population of the state make their homes and lives, make a living, develop relationships and values, govern themselves, entertain themselves, help each other, and in a multitude of ways create a distinct community. The buildings and structures and other resources on the campus reflect the contours of how that community has changed over time.

In buildings large or small, architecturally notable or not, the institutional, intellectual, and social activities associated with the various buildings and structures and other objects can make those resources historically significant under the framework for evaluation used by the National Register of Historic Places. The patterns of history with which these changes are associated are patterns not just of growth and expansion, but are more meaningful patterns of evolving purpose and structure. By recognizing the historical contexts from which these buildings and structures emerged, and the patterns and contexts which they also thereby reflect, moreover, we can not only learn more about the buildings; we can just as importantly learn more about the past from the buildings.