Windows On the Past:

Teton County, Wyoming,

Historic Resource Survey, 1999

Teton Theater, Jackson, Wyoming.

This survey was the second in a series of three (1998, 1999, 2004) and restricted its focus to properties of potential historical significance within the Town of Jackson, Wyoming.

The following is taken from the report submitted to the Teton County Historic Preservation Board. It is followed by a list of properties included in the survey. At some point in the future the survey forms will hopefully be uploaded to this site. Until that time those survey forms can be found in my report I provided for the Jackson Hole Historical Society collections.

Windows on the Past:

A Survey of Historic Buildings in Jackson, Wyoming

The inquiry into local history is at once an endeavor that attracts the energies and passions of members of a community who see about them the vestiges of earlier times and that also informs the effort to shape the future by identifying the direction of social change. It thus fulfills basic needs on both the individual and social level. In a community like Jackson, Wyoming, moreover, which finds its character and identity in past years, this inquiry is essential.

It is in this spirit that the second phase of the Teton County historic site survey was undertaken in 1998-1999. The first year, 1997-1998, focused on the rural vicinities of the county and identified a variety of structures that reflected the evolution of the county—ranches, schools, dude / guest ranch operations, homesteading and settlement, and tourist operations.[1] Just as that phase was but a beginning in the larger effort to compile information and document historic buildings in the valley, the second year’s work marks a beginning in identifying and gathering information about structures in the town of Jackson. Obviously much remains to be examined and documented in all parts of the county.

The need for the survey is large. For a town that endeavors to emulate the past of the West, much of the real past in Jackson is too often overlooked, unrecognized, or unheralded, and sometimes is even concealed and altered to conform to mythical imagery of what Jackson should have looked like. This is despite the fact that the authentic relics, the actual substances are much more fascinating and much richer than the façade of showy, tawdry, or pretentious veneers more characteristic of theme parks than of historic reality. The actual buildings from the Jackson past open a series of questions rather than stop the inquiry at a superficial level. They open windows onto the past, which above all help us see the present that much more clearly. They also indicate the course of change so that the people of Jackson can determine in a thoughtful and deliberate manner what the town will look like fifty years hence. Just as the present, from this view, is not a given, so too is the future a result of specific choices and decisions. Specifically, when considering the role of history in this town that prides itself on its connection to the western past, those decisions are often about the fate of historic buildings.

If the future of Jackson in the year 2050 seems remote, one need only consider the town of Jackson in the 1950s. Jackson is, above all, a town of the twentieth century. In the 1950s some of the original settlers of the town, and even of the valley which was settled in the last two decades of the previous century, were still living. The Teton County Historical Society held meetings and invited some of these people to speak. Their guests ranged from Rose Koops, daughter of Beaver Dick Leigh, to Harold Fabian and Dick Winger who discussed the land acquisitions of the Snake River Land Company and the turmoil surrounding them. Around a half century after the town was platted, Jackson was a community that had grown up within the memory of many of its residents. It was much like many others in the nation, especially the rural sectors; it was very much like others in Wyoming. In the 1950s the marks of the past were abundant, but the town also appeared to be changing. The isolation that had marked its early years was fading and more people from the outside came into the valley and the pressures of change gained pace and force.

The marks of the past were everywhere. Not far east of the town square, the Van Vleck house and barn seemed exempt from the currents of change and reminded the viewer to think of the origins of the town as the two buildings carried into the second half of the century ties and functions from the first half. Likewise, the buildings around the square served definite functions characteristic of the viable, close-knit community that had emerged during the previous five decades. Neighbors from near and far would still gather at the local establishments to purchase their necessities and to engage in the discourse of small town life. The white horizontal wood siding of the Clubhouse on Center and of the multiple-gabled Crabtree Hotel at the corner of King and Broadway connected the town to its earliest days. The post office was located next to Jackson Drugs—itself a building just over a decade old. The B&W Grocery operated in the downstairs of the Odd Fellows building on the same block. The Jackson Mercantile, next to the Clubhouse east of the square, and then next to it Mercill’s Store, provided hardware and men’s clothing for the townspeople. Lumley Drugs and the RJ Bar held forth south of the square. The Silver Spur Cafe and Moore’s Open Range Restaurant, their modest false-fronts painted white, overlooked the west side of the square.[2] These obviously held a certain western flavor in their construction and appearance, but they were also modern establishments, as opposed to rustic, or, what in Jackson has become known as “traditional western.”

In this way, too, the commercial sector of the town followed an unpretentious pattern. Livingston Chevrolet and Oldsmobile operated in the art deco building where LeJay’s Sportsman’s Cafe operates today. The same art deco style could be seen in the Flame Motel (where had been the Ideal Motel and which now is the Sundance Inn) and its neighbor to the east, the Roundup western wear store. The bus station on Glenwood between Broadway and Pearl, either at or near the location of Knives and Things, provided the central transportation connection with the outside world. The Spicer Garage, now the Jackson Hole Playhouse, had become the Midget Golf Course and Old Time Theater. In the three blocks between Jackson and Cache on Broadway, at least three automobile service stations and one car dealership (Riggans’ Ford, Mercury, and Jeep) operated. The streets themselves were different. Deloney was known in the 1950s, as it had been for decades, as Second Street. Gill Avenue was First Street. Mercill was North Street. South Street had not yet been renamed Hansen.

In the post World War II period Jackson was being transformed. In 1956 the Wyoming Geological Association held its annual meeting in Jackson and produced a guidebook that included an essay, written by Elizabeth Wied Hayden, on the history and current state of the valley. Hayden wrote of the history of the dominant ranching industry in the valley and calculated the progressive increase in herds:

The present number of 15,000 [cattle] has remained fairly constant for two decades at least, making it appear that the cattle business has held its own since the settling of Jackson Hole, but in recent years, since the establishment of Grand Teton National Park and the improvement of roads, the growth of tourist trade has seemed to overshadow it.[3]

Hayden continued her discussion with the nature of the change that was overtaking the valley and accurately captured the essence of the shift.

The increase in tourist travel caused by the creation of Grand Teton National Park and improved roads has made a marked change in the way of life in Jackson Hole. The old-time “dude” who remained in the valley all summer is replaced by a stream of tourists, staying a few days at most and buying groceries and a few souvenirs. To cater to them Jackson has in summer turned itself into a town of motels, filling stations, souvenir shops and restaurants, with a backbone of year-round business houses.[4]

Hayden’s own assessment of this change reflected a sense of loss that the change generated. Not only was there a fear that ranching was being displaced—though she hoped against hope that it was not so—but there was a corresponding decline in the commitment to the community, to civic activity that was evident in the new trend; she hoped also that that commitment could be revived:

Though Jackson Hole is no doubt more prosperous than it formerly was, due to the phenomenal rise in tourist travel, we trust that cattle and dude ranching, with its cattle drives and cow camps, its dudes on horseback and its local talent rodeos, will never have to give way. It has been a basic and colorful part of the Jackson Hole pattern too long to permit that to come to pass.

An effort is being made to secure a more stable, year-round economy for Jackson Hole, encouraging the inhabitants to live there throughout the year and to devote more time to civic projects.[5]

This hopeful view of Jackson retaining its ranching and small town character more than four decades ago may seem quaint and innocent—naïve even—from the perspective of 1999, but its optimism about the continuity of the past simply rested on the notion that what should prevail will in fact be what comes about. While it would be easy to offer a different assessment at the end of the century, and while a vigorous and close discussion of the course of change in the town should take place, the one basic fact is that the fundamental pattern of change in the past needs to be examined closely. By looking into the past we can see more clearly where Jackson has gone, and therefore exactly what it is like today; by studying the past we can see processes at work by which the present came into being.

So this survey is a beginning in two ways. One way is in the development of a record of buildings of historical significance in the commercial area of Jackson. The other is in the promotion of a discussion of and sensitivity to the history of the community more generally. While the current inventory includes only commercial / public structures, it has attempted to select a variety of buildings to suggest a range of community activities and developments. Thus it includes the centers of community energy, both official and unofficial (most notably the Clubhouse), the indications of outside authority (like the Forest Service building), the vestiges of early settlement (the Karns Cabin), the rise of non-commercial associations (like the American Legion and the IOOF) and the importance of religion (the LDS Ward Meeting House), the growth of a larger sense of community value and culture (the library and the historical society), as well as the role of commercial recreation of different kinds in the community (the Jackson Theater and the Million Dollar Cowboy Bar), in addition to the retail commercial operations (like the Deloney Store and the Jackson Drug Company and the Spicer Garage). Also included is one site that is not a building but is an example of community activity to create an artifact of landscape architecture in the center of town—the Town Square (or Washington Park). Other buildings nearby remain to be inventoried, and some remain even to be discovered and listed. Work by the Teton County Historic Preservation Board preceded this study, especially in the development of an extensive windshield survey, and more work will doubtless follow this to generate a comprehensive inventory.

[1] Michael Cassity, Jackson Hole Palimpsest: A Survey of Historic Buildings in Teton County, Wyoming 1997-1998 (study prepared for the Teton County Historic Preservation Board, August 1998).

[2] A quick view of the business part of town can be gained from the map of the town prepared by Quita Pownall, daughter of Harrison Crandall, in the Jackson Hole Guide, August 29, 1957. This is one of the first, and possibly the first, annual picture map to show tourists the way to various establishments around town.

[3] Elizabeth Wied Hayden, “History of Jackson Hole,” Wyoming Geological Association, 11th Annual Field Conference, 1956 (n.p.: n.d.), 17. This is also referred to as the 1956 WGA Guidebook.

[4] Hayden, “History of Jackson Hole,” 18.

[5] Hayden, “History of Jackson Hole,” 18.

It is in this spirit that the second phase of the Teton County historic site survey was undertaken in 1998-1999. The first year, 1997-1998, focused on the rural vicinities of the county and identified a variety of structures that reflected the evolution of the county—ranches, schools, dude / guest ranch operations, homesteading and settlement, and tourist operations.[1] Just as that phase was but a beginning in the larger effort to compile information and document historic buildings in the valley, the second year’s work marks a beginning in identifying and gathering information about structures in the town of Jackson. Obviously much remains to be examined and documented in all parts of the county.

The need for the survey is large. For a town that endeavors to emulate the past of the West, much of the real past in Jackson is too often overlooked, unrecognized, or unheralded, and sometimes is even concealed and altered to conform to mythical imagery of what Jackson should have looked like. This is despite the fact that the authentic relics, the actual substances are much more fascinating and much richer than the façade of showy, tawdry, or pretentious veneers more characteristic of theme parks than of historic reality. The actual buildings from the Jackson past open a series of questions rather than stop the inquiry at a superficial level. They open windows onto the past, which above all help us see the present that much more clearly. They also indicate the course of change so that the people of Jackson can determine in a thoughtful and deliberate manner what the town will look like fifty years hence. Just as the present, from this view, is not a given, so too is the future a result of specific choices and decisions. Specifically, when considering the role of history in this town that prides itself on its connection to the western past, those decisions are often about the fate of historic buildings.

If the future of Jackson in the year 2050 seems remote, one need only consider the town of Jackson in the 1950s. Jackson is, above all, a town of the twentieth century. In the 1950s some of the original settlers of the town, and even of the valley which was settled in the last two decades of the previous century, were still living. The Teton County Historical Society held meetings and invited some of these people to speak. Their guests ranged from Rose Koops, daughter of Beaver Dick Leigh, to Harold Fabian and Dick Winger who discussed the land acquisitions of the Snake River Land Company and the turmoil surrounding them. Around a half century after the town was platted, Jackson was a community that had grown up within the memory of many of its residents. It was much like many others in the nation, especially the rural sectors; it was very much like others in Wyoming. In the 1950s the marks of the past were abundant, but the town also appeared to be changing. The isolation that had marked its early years was fading and more people from the outside came into the valley and the pressures of change gained pace and force.

The marks of the past were everywhere. Not far east of the town square, the Van Vleck house and barn seemed exempt from the currents of change and reminded the viewer to think of the origins of the town as the two buildings carried into the second half of the century ties and functions from the first half. Likewise, the buildings around the square served definite functions characteristic of the viable, close-knit community that had emerged during the previous five decades. Neighbors from near and far would still gather at the local establishments to purchase their necessities and to engage in the discourse of small town life. The white horizontal wood siding of the Clubhouse on Center and of the multiple-gabled Crabtree Hotel at the corner of King and Broadway connected the town to its earliest days. The post office was located next to Jackson Drugs—itself a building just over a decade old. The B&W Grocery operated in the downstairs of the Odd Fellows building on the same block. The Jackson Mercantile, next to the Clubhouse east of the square, and then next to it Mercill’s Store, provided hardware and men’s clothing for the townspeople. Lumley Drugs and the RJ Bar held forth south of the square. The Silver Spur Cafe and Moore’s Open Range Restaurant, their modest false-fronts painted white, overlooked the west side of the square.[2] These obviously held a certain western flavor in their construction and appearance, but they were also modern establishments, as opposed to rustic, or, what in Jackson has become known as “traditional western.”

In this way, too, the commercial sector of the town followed an unpretentious pattern. Livingston Chevrolet and Oldsmobile operated in the art deco building where LeJay’s Sportsman’s Cafe operates today. The same art deco style could be seen in the Flame Motel (where had been the Ideal Motel and which now is the Sundance Inn) and its neighbor to the east, the Roundup western wear store. The bus station on Glenwood between Broadway and Pearl, either at or near the location of Knives and Things, provided the central transportation connection with the outside world. The Spicer Garage, now the Jackson Hole Playhouse, had become the Midget Golf Course and Old Time Theater. In the three blocks between Jackson and Cache on Broadway, at least three automobile service stations and one car dealership (Riggans’ Ford, Mercury, and Jeep) operated. The streets themselves were different. Deloney was known in the 1950s, as it had been for decades, as Second Street. Gill Avenue was First Street. Mercill was North Street. South Street had not yet been renamed Hansen.

In the post World War II period Jackson was being transformed. In 1956 the Wyoming Geological Association held its annual meeting in Jackson and produced a guidebook that included an essay, written by Elizabeth Wied Hayden, on the history and current state of the valley. Hayden wrote of the history of the dominant ranching industry in the valley and calculated the progressive increase in herds:

The present number of 15,000 [cattle] has remained fairly constant for two decades at least, making it appear that the cattle business has held its own since the settling of Jackson Hole, but in recent years, since the establishment of Grand Teton National Park and the improvement of roads, the growth of tourist trade has seemed to overshadow it.[3]

Hayden continued her discussion with the nature of the change that was overtaking the valley and accurately captured the essence of the shift.

The increase in tourist travel caused by the creation of Grand Teton National Park and improved roads has made a marked change in the way of life in Jackson Hole. The old-time “dude” who remained in the valley all summer is replaced by a stream of tourists, staying a few days at most and buying groceries and a few souvenirs. To cater to them Jackson has in summer turned itself into a town of motels, filling stations, souvenir shops and restaurants, with a backbone of year-round business houses.[4]

Hayden’s own assessment of this change reflected a sense of loss that the change generated. Not only was there a fear that ranching was being displaced—though she hoped against hope that it was not so—but there was a corresponding decline in the commitment to the community, to civic activity that was evident in the new trend; she hoped also that that commitment could be revived:

Though Jackson Hole is no doubt more prosperous than it formerly was, due to the phenomenal rise in tourist travel, we trust that cattle and dude ranching, with its cattle drives and cow camps, its dudes on horseback and its local talent rodeos, will never have to give way. It has been a basic and colorful part of the Jackson Hole pattern too long to permit that to come to pass.

An effort is being made to secure a more stable, year-round economy for Jackson Hole, encouraging the inhabitants to live there throughout the year and to devote more time to civic projects.[5]

This hopeful view of Jackson retaining its ranching and small town character more than four decades ago may seem quaint and innocent—naïve even—from the perspective of 1999, but its optimism about the continuity of the past simply rested on the notion that what should prevail will in fact be what comes about. While it would be easy to offer a different assessment at the end of the century, and while a vigorous and close discussion of the course of change in the town should take place, the one basic fact is that the fundamental pattern of change in the past needs to be examined closely. By looking into the past we can see more clearly where Jackson has gone, and therefore exactly what it is like today; by studying the past we can see processes at work by which the present came into being.

So this survey is a beginning in two ways. One way is in the development of a record of buildings of historical significance in the commercial area of Jackson. The other is in the promotion of a discussion of and sensitivity to the history of the community more generally. While the current inventory includes only commercial / public structures, it has attempted to select a variety of buildings to suggest a range of community activities and developments. Thus it includes the centers of community energy, both official and unofficial (most notably the Clubhouse), the indications of outside authority (like the Forest Service building), the vestiges of early settlement (the Karns Cabin), the rise of non-commercial associations (like the American Legion and the IOOF) and the importance of religion (the LDS Ward Meeting House), the growth of a larger sense of community value and culture (the library and the historical society), as well as the role of commercial recreation of different kinds in the community (the Jackson Theater and the Million Dollar Cowboy Bar), in addition to the retail commercial operations (like the Deloney Store and the Jackson Drug Company and the Spicer Garage). Also included is one site that is not a building but is an example of community activity to create an artifact of landscape architecture in the center of town—the Town Square (or Washington Park). Other buildings nearby remain to be inventoried, and some remain even to be discovered and listed. Work by the Teton County Historic Preservation Board preceded this study, especially in the development of an extensive windshield survey, and more work will doubtless follow this to generate a comprehensive inventory.

[1] Michael Cassity, Jackson Hole Palimpsest: A Survey of Historic Buildings in Teton County, Wyoming 1997-1998 (study prepared for the Teton County Historic Preservation Board, August 1998).

[2] A quick view of the business part of town can be gained from the map of the town prepared by Quita Pownall, daughter of Harrison Crandall, in the Jackson Hole Guide, August 29, 1957. This is one of the first, and possibly the first, annual picture map to show tourists the way to various establishments around town.

[3] Elizabeth Wied Hayden, “History of Jackson Hole,” Wyoming Geological Association, 11th Annual Field Conference, 1956 (n.p.: n.d.), 17. This is also referred to as the 1956 WGA Guidebook.

[4] Hayden, “History of Jackson Hole,” 18.

[5] Hayden, “History of Jackson Hole,” 18.

Resources Included in the Survey

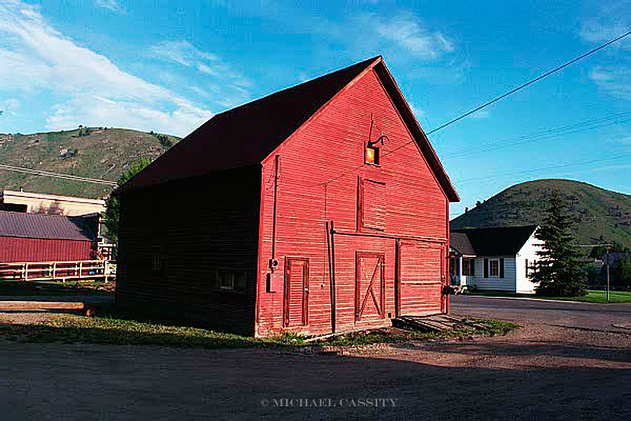

VanVleck Barn, Jackson, Wyoming.

American Legion Building

The Clubhouse

Cowboy Bar

Deloney Building / Spicer Garage / Jackson Hole Playhouse

Deloney Store / Jackson Hole Museum

IOOF Lodge

Jackson Drug Company

Karns Cabin

LDS Ward Meeting House / Masonic Lodge

Teton County Historical Society Building / Coey Cabin

Teton County Library / Huff Memorial Library

Teton National Forest Headquarters Building

Teton Theater

Town Square / Washington Park